A Trek in

the Langtang

by John Wallack

[published in Thin Air

Volume 5 Number 1 January 1993]

Looking for some high peaks, but something less than an

expedition? Nepal's Langtang Himal offers several interesting climbing

possibilities as well as a great approach trek. Our interest in this area was

kindled in 1989 when Kris and I saw the snow-capped peaks from the plane as we

flew into Kathmandu from an Everest-area trek. Because the Langtang area is only

about 30 miles north of Kathmandu, the logistics of getting there appeared to be

minimal. So this year, when our climbing buddy Deac Lancaster broke his leg six

weeks prior to our departure for Mera Peak, Kris and I decided to opt for the

shorter Langtang trek.

The Trek

The trek into the Langtang can be approached either from the Trisuli river

valley by bus or taxi to the town of Dhunche, or the more interesting approach

from the south via the Thare Danda. The trek in from Sundarijal follows the

crests of several ridges offering excellent vistas. Our proposed plan was taken

directly from the description in Bill O'Connor's Trekking Peaks of Nepal: 7 days

trekking from Sundarijal to Kyangjin, climb from Kyangjin, then exit via Ganja

La back to Sundarijal. Although the trekking agency agreed to this plan by FAX,

when we got to Kathmandu they recommended taking an extra day on the way in and

considering an exit via Dhunche. We agreed to this and later we felt that it was

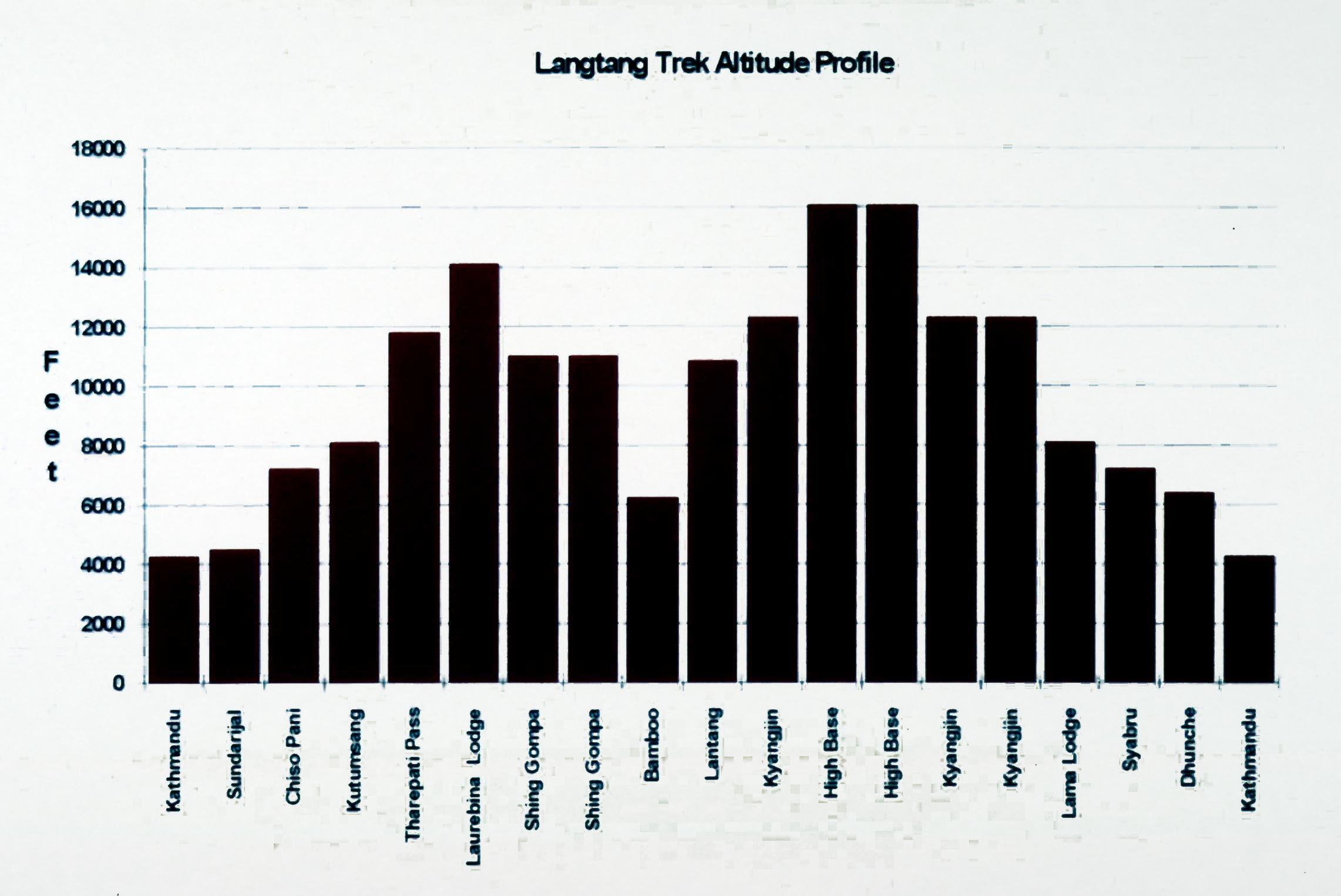

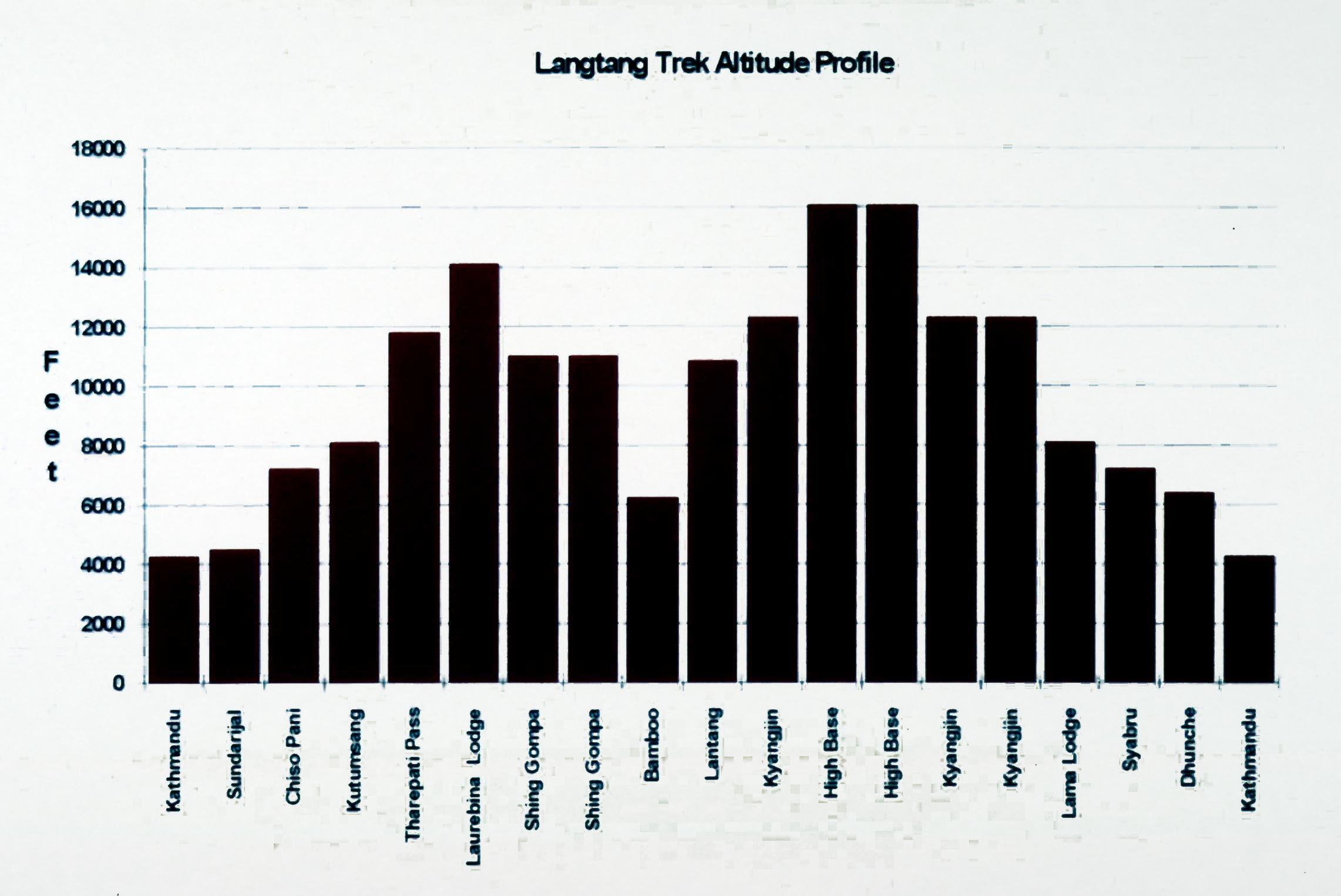

good advice. The schedule that we actually followed is shown in the altitude

profile.

We had a great support crew for the trek. There were three Sherpas: Sherku, the

sirdar, Karma, the cook, and Nagtbar, the cooks helper. We started off with six

porters, which was reduced to four after 5 days and down to two after nine days.

We were concerned about the bulk of our 20 kg duffels as single loads as we

packed them, but at the trailhead a porter promptly tied both duffels together

to make a single load!

The diversity of this eighteen day trek was amazing. There were

significant elevation gains and losses through the bright green terraced

foothills. In the Tamang villages along the way, children were hauling loads of

hay from the fields. Corn and millet was drying in the sun on mats. A few days

hiking along the ridges took us from terraced farmland to the mountainous

terrain of the 14,000' Thare Danda. A climb over Laurebina Pass (4609m/ 15,100')

brought us to the lakes and shrine at Gosainkund.

A spectacular trail down the Chalang Pati Danda passed through

the ridge town of Syabru, which was a pastoral scene of harvesting millet and

corn from the terraced fields. Women in tradition dress were threshing the dried

millet with hinged flails. The grain was then separated from the chaff by

tossing it with round, flat baskets. From this point you could look over the

3000' gorge of the Langtang Kola where it joins the Trisuli Ganga.

The trek from Syabru up the Langtang gorge dropped down below 2000m, and took us

into bamboo forests. Here we saw white faced monkeys in the trees, six foot

honey combs hanging on rock cliffs, and a herd of mountain goats. A couple of

days hiking brought us above timber line into the upper Langtang valley.

Kyangjin

The village of Kyangjin was a fine base camp for the upper Langtang valley.

At 12,300', the village is surrounded by snow-covered peaks, and is the site of

a yak cheese factory, the Kyangjin Gompa and several hotels with campsites.

There are several possibilities for day trips from this base which do not

require climbing permits. During my attempt at Naya Kanga, Kris and Karma

climbed Phushung (4400m/14,436') just north of Kyangjin. From there they climbed

the ridge up to Kyimoshung (4640m/15,223') and then up to a point on the same

ridge at (4773m/15,659'). This route offers spectacular views of Naya Kanga and

other neighboring peaks.

There are several other possibilities in the valley. Further

east on the north side of the valley is Tsergo Ri, (4984m/16,352'), requiring a

full day's effort from Kyangjin. To the east of Tsergo Ri, are two glaciated

peaks that do not require climbing permits. The southernmost is Yala Peak

(5520m/18,110'). About 1.3km north along the same ridge is Tsergo Peak (5749m/

18,862'). To climb either of these peaks, a high camp is typically set up at

Yala Kharka (4800m/15,748') and the climbing party returns to Kyangjin after the

climb.

Naya Kanga (5846m/19,180'), a trekking peak, is located south of Kyangjin west

of Ganja La. As a Category B trekking peak, a $150 permit is required. The

standard approach to this peak is to establish a high base camp west of the

route up to Ganja La and climb from there. Some notes from my attempt of Naya

Kanga follow.

Naya Kanga

We woke Saturday about 6AM. Outside everything was crystal cold. The

thermometer on my pack registered about 8 degrees Fahrenheit. Nagtbar immediately

started melting snow. He made a marvelous kettle of coffee and some

noodles-ala-fried-egg. The night before between the confusion over where to set

up the high camp and a feeling of total exhaustion, I had decided to forego the

3AM climb in the dark. I had doubts about continuing the climb at all. Things

looked pretty dismal at 8PM as we chipped snow with the ice ax for melting. I

was still weak from the flu that I caught on the trek in and Sherku, my sherpa

climbing companion, was not familiar with the peak. But, drinking hot coffee at

sunrise things looked better. I sat there looking at Naya Kanga and realized

that we had literally stumbled on the normal site for the high camp the night

before. The summit looked so close, I asked Sherku if he was up for giving it a

try. He said sure, so at 6:45 we stared a climb that we should have started at

4AM.

We were camped just below the terminal moraine of the hanging

glacier on the northeast ridge. The standard route, as described by O'Connor,

went up from the high camp toward Ganja La and then across the glacier shelf to

the northeast ridge. Having been to Ganja La the night before, we struck out

directly across the terminal moraine as it was more direct. I was a bit

apprehensive, as there is usually some hidden obstacle disqualifying an apparent

shortcut as a standard route. When we gained the top of the moraine, we were

looking over the bowl to the glacier shelf and a rock wall to the right. We

proceeded through the bowl-shaped moonscape of rock and sand hoping the climb to

the right would go. It wasn't as hard as it looked and at 10AM we were level

with the top of the glacier shelf taking a break.

The route up a broad couloir to the col at the base of the northeast ridge was

filled with inconsistent snow. It would vary from boiler plate to thigh-deep

trudging. The views of Tillman's Fluted Peak, or Gangchempo, from the ridge were

great. At the top of the couloir, we roped up and started up the ice nose. This

was the steepest part of the climb. As we gained elevation along the ridge, the

views of the Langtang valley opened up to a sea of snow-capped peaks. What a

fine way to spend a day! The going was slow on the steep snow. At 1:30PM we were

still 100' below the top of the nose and our time had run out. At the rate we

were climbing, it appeared as though it would still require a couple of hours to

reach the summit. Reluctantly, we turned back, reaching high camp quite

exhausted at 6:30PM.

Reading & Maps

H. W. Tillman's Nepal Himalaya describes his exploration of the

area in 1949 and provides some interesting background reading. Trekking guides

by Swift and Bezruchka both contain trail information for the Langtang area,

although the best reference for our trek was Bill O'Connor's Trekking Peaks of

Nepal. The trek route is described in greater detail and the route on Naya Kanga

is given. A good planning map for the trek is the Schneider Series

Helambu-Lantang (1:100 000).The best maps for the Langtang valley are the new

('90) Alpenvereinskarte Langtang Himal (1:50 000) east & west.